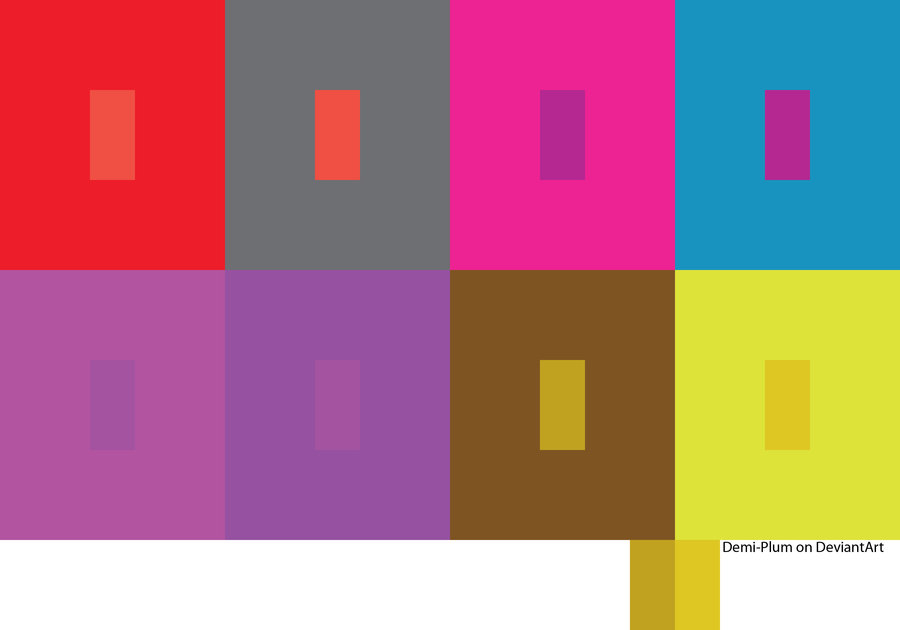

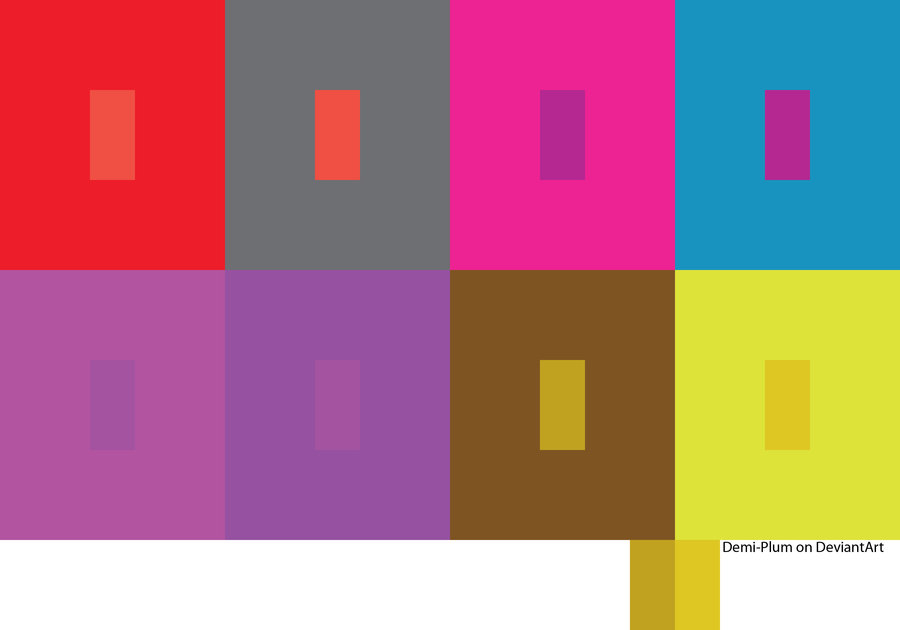

Simultaneous Contrast

Image by Demi-Plum on DeviantArt

When two colors appear side by side, it changes our perception of them. Graphic designers and artists use this effect called simultaneous contrast. Sometimes when I think about passages of scripture they seem to exhibit simultaneous contrast as well. Different aspects of the story will leap out at me depending on which stories I hold in my mind in close proximity. I’ll show you what I mean.

It started when I read Mark 11: 12-25, where Jesus is driving the money-changers and vendors out the temple. Wrapped around the cleansing of the temple is the cursing of the fig tree in two parts: first the seemingly unjustified cursing, then, the following day, Jesus explanation of the withered tree. Here’s how it goes:

On the following day, when they came from Bethany, he was hungry. And seeing in the distance a fig tree in leaf, he went to see if he could find anything on it. When he came to it, he found nothing but leaves, for it was not the season for figs. And he said to it, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” And his disciples heard it.

And they came to Jerusalem. And he entered the temple and began to drive out those who sold and those who bought in the temple, and he overturned the tables of the money-changers and the seats of those who sold pigeons; and he would not allow any one to carry anything through the temple. And he taught, and said to them, “Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations’? But you have made it a den of robbers.” And the chief priests and the scribes heard it and sought a way to destroy him; for they feared him, because all the multitude was astonished at his teaching. And when evening came they went out of the city.

As they passed by in the morning, they saw the fig tree withered away to its roots. And Peter remembered and said to him, “Master, look! The fig tree which you cursed has withered.” And Jesus answered them, “Have faith in God. Truly, I say to you, whoever says to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and cast into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart, but believes that what he says will come to pass, it will be done for him. Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against any one; so that your Father also who is in heaven may forgive you your trespasses.”

I know I’ve heard this passage a hundred times, and I’ve always heard it as a story about the power of prayer (Have faith and cast that mountain into the sea!), but I’d never realized that the money-changers were inside a fig tree sandwich, so to speak. I wondered why Mark would write it that way. Then I noticed that the two incidents both involve Jesus teaching about prayer.

“Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations’? But you have made it a den of robbers.”

And

“…Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against any one; so that your Father also who is in heaven may forgive you your trespasses.”

That phrase “whenever you stand praying” reminded me of the Amidah–the central prayer in a Jewish service, recited in services three times daily during the week, and also at Sabbath and holiday services. Amidah is Hebrew for “standing,” and this prayer is recited while standing with feet firmly together so as to imitate the angels, “whose legs were straight” in Ezekiel 1: 7.

But here is the bit that stood out for me, the Amidah is said during services–which would be held in the temple or in a synagogue–in a house of prayer. And the Amidah, which is also called the Shmoneh Esreh–the Eighteen Blessings–includes praise, petitions, and thanksgiving. The worshiper asks for God’s forgiveness, compassion, and justice, but the prayer says nothing about the worshiper forgiving anyone else. To say “whenever you stand praying, forgive” represents a change, I suspect, and that, of course, reminded me of these familiar words from Matthew 6:

And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors

So maybe these incidents are linked because they are about prayer. Because we need to know how to pray and to be mindful about how we treat a house of prayer, and, yes, to believe in the power of prayer.

But why did Jesus have to kill the fig tree? Was it just to make a point? It wasn’t even fig season. Wasn’t he expecting a bit too much? Is this an illustration of his anger before he even reached the temple? It seems almost petulant.

And thinking about petulance and withered plants put me in mind of another story–this time from Jonah (Jonah 3:10; 4: 1-11)

When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God repented of the evil which he had said he would do to them; and he did not do it.

But it displeased Jonah exceedingly, and he was angry. And he prayed to the Lord and said, “I pray thee, Lord, is not this what I said when I was yet in my country? That is why I made haste to flee to Tarshish; for I knew that thou art a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and repentest of evil. Therefore now, O Lord, take my life from me, I beseech thee, for it is better for me to die than to live.” And the Lord said, “Do you do well to be angry?” Then Jonah went out of the city and sat to the east of the city, and made a booth for himself there. He sat under it in the shade, till he should see what would become of the city.

And the Lord God appointed a plant, and made it come up over Jonah, that it might be a shade over his head, to save him from his discomfort. So Jonah was exceedingly glad because of the plant. But when dawn came up the next day, God appointed a worm which attacked the plant, so that it withered. When the sun rose, God appointed a sultry east wind, and the sun beat upon the head of Jonah so that he was faint; and he asked that he might die, and said, “It is better for me to die than to live.” But God said to Jonah, “Do you do well to be angry for the plant?” And he said, “I do well to be angry, angry enough to die.” And the Lord said, “You pity the plant, for which you did not labor, nor did you make it grow, which came into being in a night, and perished in a night. And should not I pity Nin′eveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left, and also much cattle?”

“You pity the plant…” I do pity the plant. Sometimes it’s easier to pity the plant than the people making money off of other people’s piety. It’s so painful when a tree is cut down. Do I feel that much compassion for the TV evangelist who encourages the faithful to call in their pledges? Would it offend my sense of justice if God ended up pitying folks who, given what God has already said, clearly deserve a bit of wrath? Would that make me angry enough to die?

So what’s the point? I’m not sure. All I know is that an interesting thing happens when you put these stories side by side. God seems to be using plants to comment on situations where we might be tempted to point the finger and get angry about other people’s sins–where we might get a little rigid in our thinking about justice.

Whenever you stand praying, forgive. That’s all I know for sure. I don’t think it’s wrong to pity the plants. I think I know my right hand from my left. I hope I’m not one of the cattle.