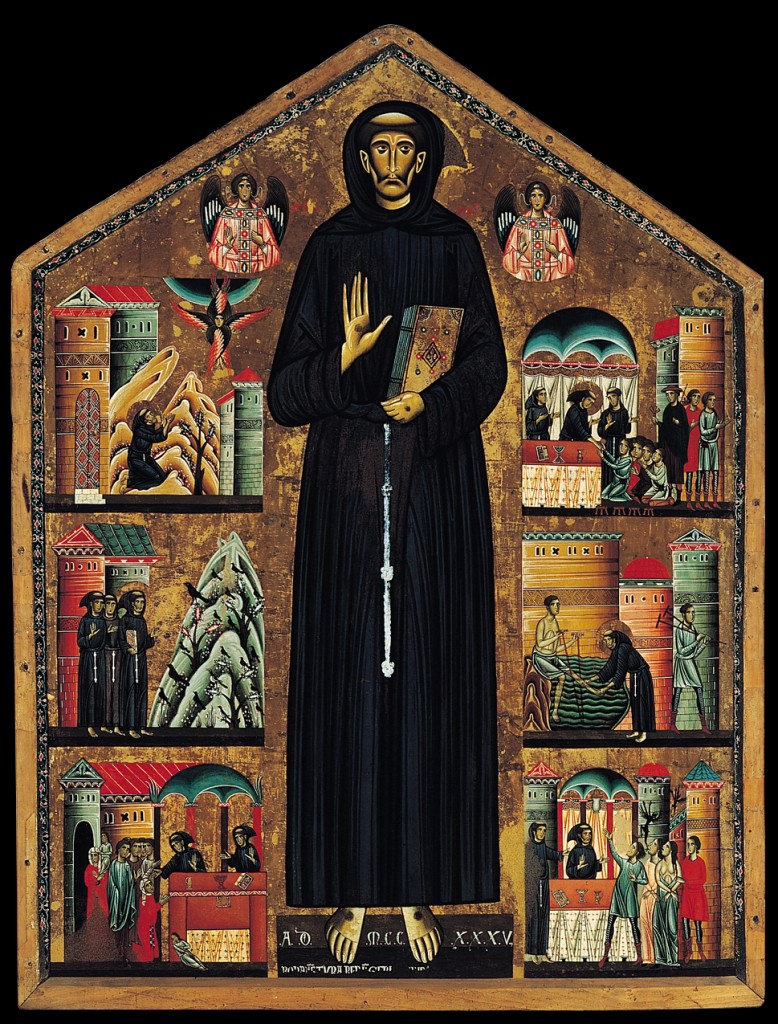

St. Jude Thaddeus, Georges de La Tour, 1650

Today is the feast day of St. Jude, the patron saint of lost causes, the Chicago police department and many hospitals. I first learned of St. Jude watching The Untouchables, a movie about Eliot Ness’ pursuit of Al Capone during Prohibition. In that movie, the team is enjoying supper after a successful raid when Ness sees Malone, a long-time beat cop, holding a saint’s medal on a chain.

“What is that?” he asks.

Malone responds with surprise, “What is that?”

“Yes, what is it?”

“God, I’m with the heathen.” Showing Ness the medal, Malone explains, “That is my call box key, and that is St. Jude.”

Stone, a young Italian on the team says, “Santo Jude. He’s the patron saint of the lost causes.”

“And policemen,” says Malone.

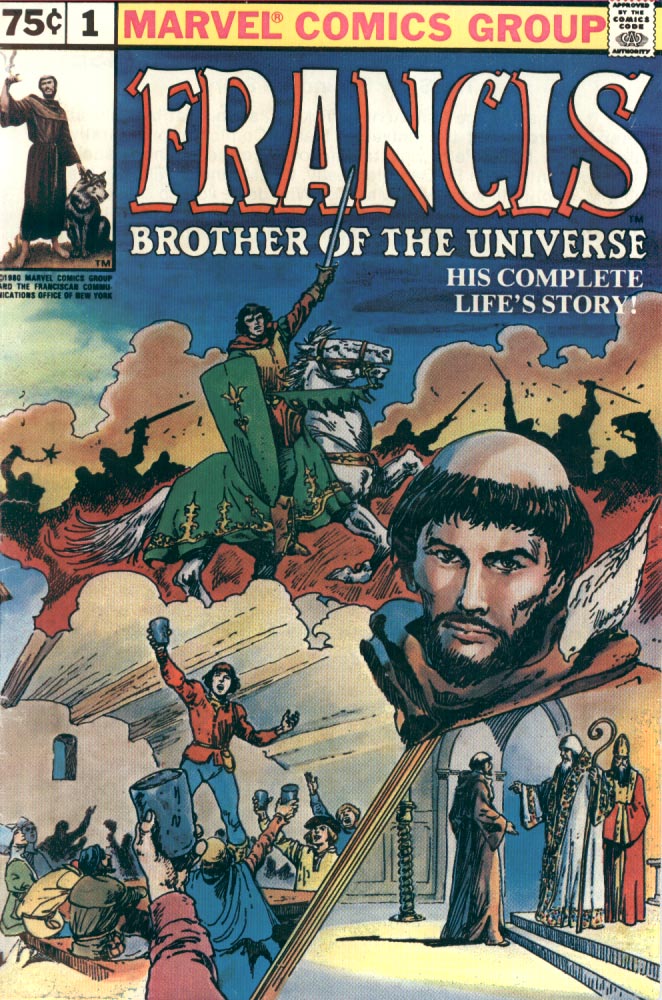

If you grew up in the Protestant tradition as I did (and are thus among Malone’s heathen), the origin stories of heavenly advocates can be startling. They certainly represent some of humanity’s most creative attempts to explain God’s work in the world, and to honor the holy people among us.

So why did St. Jude get saddled with the lost causes, and how did those causes come to be their own category among all the professions and diseases that are identified with other saints?

Wikipedia gives us an amusing explanation that I’ve found repeated on several other web sites. I have no idea how this tale came to be, or indeed if it is a traditional or modern fabrication. Still, it’s a great story, and with that caveat, I’ll share it:

St. Jude is known as the patron saint of lost causes amongst Roman Catholics. This is due to the tradition that, because his name was similar to the traitor Judas Iscariot, few, if any faithful Christians prayed for his intervention, out of the mistaken belief that they would be praying to Judas Iscariot. As a result, St. Jude was little used, and so became eager to assist any who asked him, to the point of intervening in the most dire of circumstances. The Church also wanted to encourage veneration of this “forgotten” disciple. Therefore, the Church maintained that St. Jude would intervene in any lost cause to prove his saintliness and zeal for Christ, and thus St. Jude became the patron of lost causes.

I laugh to think of St. Jude with nothing to do in heaven–no prayers coming in–eagerly taking on dire problems that no other saints would touch. Surely this is one of those instances of imagination run wild. Nevertheless, I do think that recognizing the place of lost causes in the life of the Church and asking for a bit of help is good and appropriate. We’ll always have the poor. And human nature. There’s a lot in this world that could bring a body to despair.

So, as I think about St. Jude, I’m reminded of another movie where a character named Jefferson Smith says lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for; his advocate, Clarissa Saunders, says they’re taken up by fools with faith in something bigger. On this feast day, that sounds about right to me.

…the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. (1 Corinthians 1)