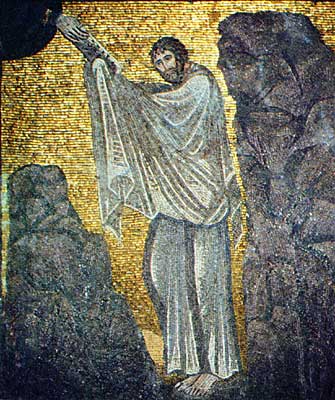

Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have gotten a man with the help of the Lord.” And again, she bore his brother Abel. Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel brought of the firstlings of his flock and of their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell. The Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is couching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it.”

Cain said to Abel his brother, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel, and killed him. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?” And the Lord said, “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.” Cain said to the Lord, “My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou hast driven me this day away from the ground; and from thy face I shall be hidden; and I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will slay me.” Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! If any one slays Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, lest any who came upon him should kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, east of Eden.

Have you ever heard a sermon preached on this scripture? I’m not sure I have, but I’d like to. The more I look at this passage the more complicated and interesting it becomes. I know I’m not alone in this fascination. John Steinbeck and many rabbis have spent time thinking about it. Bruce Springsteen points to it. There’s even a reference in the game Batman: Arkham City. Perhaps we should take a look. There’s more to Cain and Abel than “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

Much of what interests me about this story has to do with language and double meanings. Before we dig in, you need to know that a few chapters back in Genesis, Adam (whose name carries linguistic associations with the words “man” and “red” is created from the red earth (adamah). Man and earth are interdependent. Adam and Eve care for the garden and live on its produce, but after the Fall, the earth is cursed and Adam’s relationship with it becomes a struggle. The consequences of sin are not borne by Adam and Eve alone. God says to Adam:

…cursed is the ground because of you;

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you;

and you shall eat the plants of the field.

In the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread

till you return to the ground,

for out of it you were taken;

you are dust,

and to dust you shall return.

from Genesis 3

When we come to the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis 4, Cain, the tiller of the soil, becomes angry when God rejects his offering in favor of his younger brother’s firstlings. Cain lures Abel out to a field, where he kills his brother. The ground opens its mouth and receives Abel’s blood from Cain’s hand, but the earth cannot conceal the crime. God asks, “Where’s Abel?” and receives Cain’s insolent answer. Abel’s blood cries out, and the earth also speaks in a manner, with a curse. Having opened its mouth to take in blood, the ground will no longer produce food:

…you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.

Cain’s sin and his curse are built on his father’s. Cain’s relationship with the earth becomes so broken that he must wander, a fugitive from Eden. He is separated from the land of his birth, and he must leave God’s presence. Yet, even in exile, Cain is under God’s protection. God’s reach, his mercy, extends beyond Eden, into the land of Wandering (Nod).

There’s much more to tease out of this story. So much we could talk about. I wonder why some translations say sin is “crouching” at the door (which sounds like it is ready to spring) while the KJV and RSV say sin “lieth at the door” or is “couching” (which sounds less like an attack and more like sin has taken up residence). And what about after Cain leaves Eden? The Bible says he gets married and has a son, and then he and his wife build the first city, Enoch. How are we to think about cities, if they came into being because sinful Cain can no longer farm the earth? And why then do we long for Zion, the heavenly city, and not for a return to the Garden? What happens when we return to the dust from which we were taken?